This page holds a collection of material from the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry (1956). It includes the final report and, more interestingly, the transcripts of four meetings (and one preliminary organising meeting) at which the members of the Commission heard evidence from a diverse array of stakeholders in Nyasaland’s fishing industry. These pages of transcribed testimony will be a rich resource for anyone interested in fishing in colonial Malawi. They will also provide broader insight into late colonial Southern Africa’s society, politics, and economy.

Downloads beneath the introduction below.

An Introduction to the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry (1956) by Milo Gough

In the mid-1950s, the fishing industry around the south-east arm of Lake Malawi, then known as Lake Nyasa, was expanding. Both non-African commercial and nascent African-led firms were pulling more fish from Lake Nyasa and nearby Lake Chilwa than ever before. More and more people were absorbed into the industry at all levels: as labour for the more significant fishing concerns, as independent traders plying the routes between the lake shore and market by bicycle, or as consumers in lakeside villages, tea plantations, and colonial towns. Yet, even as the industry grew, it was understood to be falling short of its full potential due to several structural limitations, including the recent introduction of lake side price controls on the back of the 1955 Native Authority Act and the ban on foreign export of fish implemented in response to the 1949 famine. So, in early 1956, recently elected nationalist politicians put pressure on the colonial government to support the fishing industry, a sector seen as crucial to the future of African-led economic development. Furthermore, the young and charismatic leaders of the nationalist movement, Kanyama Chiume and Henry Chipembere, had close familial links to the fishing industry. As argued by historian Wiseman Chirwa (1996: 374), to these men, the inquiry was both a question of national and personal importance.1 The Commission was appointed on the 24th of April 1956, having emerged from the intersection of nationalist politics and the increasingly important role of fishing in the late colonial economy of Nyasaland.

The Commission was chaired by J.B. Hobson, Nyasaland’s Attorney General. He was joined by J.H. Ingham, Secretary for African Affairs; F.G. Collins, Non-African Member of the Legislative Council; N.D. Kwenje, African Member of the Legislative Council; and H.J.H. Borley, Director of the Game, Fish & Tsetse Control Department. In collecting evidence and testimony from stakeholders in the industry, these five men had five aims, referred to as ‘terms of reference’:

1. to assess as far as possible the total internal demand for locally caught fish at various price levels and to relate this to the actual quantities caught by the existing fishing concerns, both non-African and African in recent years;

2. to consider the adequacy of the present arrangements of the fishing concerns, both non-African and African, for the storage, preservation, curing, transport, distribution and sale of locally caught fish, and advise how they might be improved;

3. to assess whether fish caught locally can economically compete with imported fish;

4. to advise whether the general or limited export of locally caught fish to the Rhodesias would be in the public interest of the Protectorate;

5. to advise whether the price control in respect of fish would be practicable or desirable.

The final Report of the Inquiry, which contains their analysis of the voluminous evidence, followed these aims closely. However, whilst responding to these aims, the evidence itself was less constrained by them. Instead, testimony seemed to be guided, in part at least, by the concerns of each interlocutor and the groups he claimed to represent.

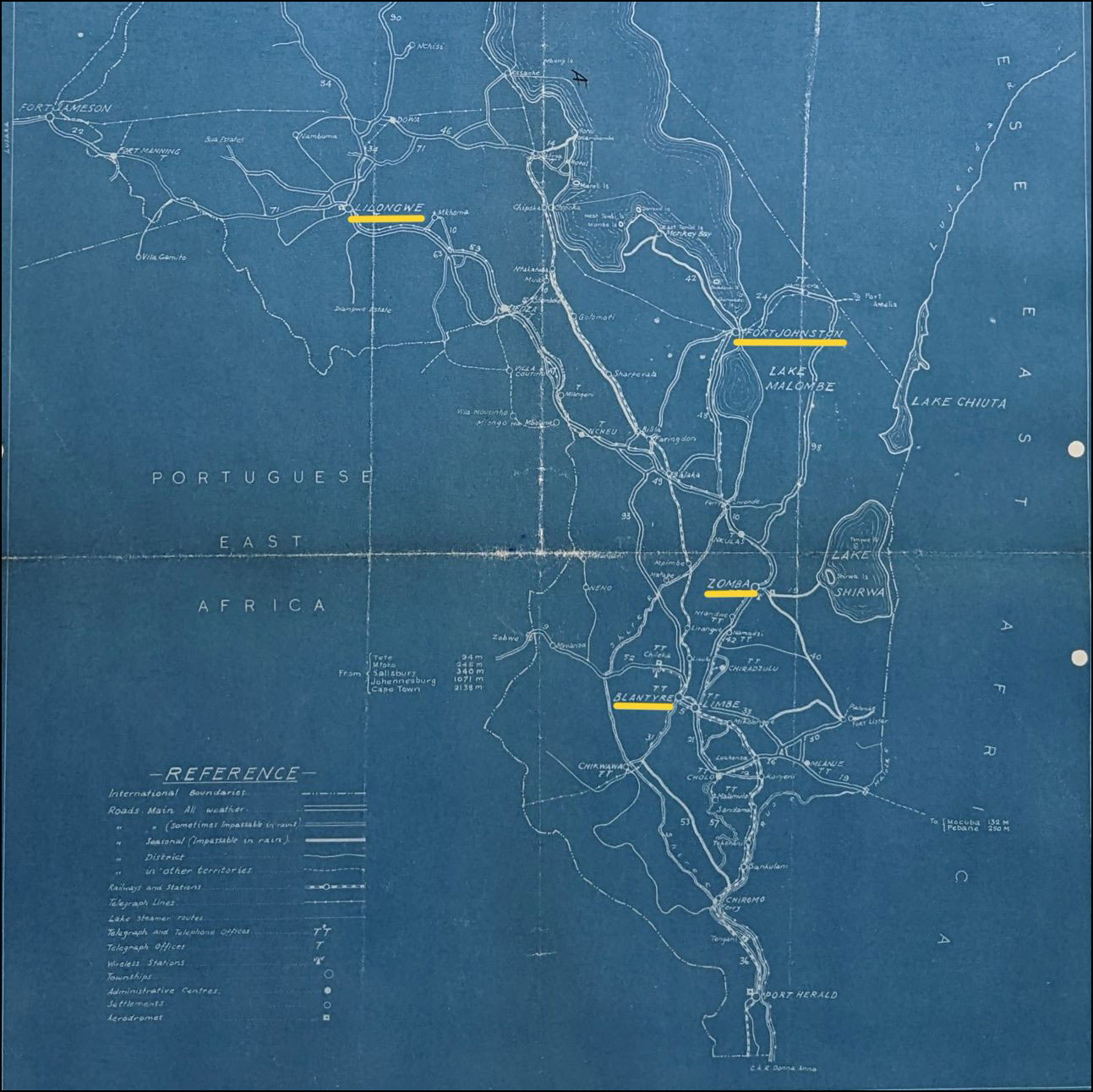

After a preliminary meeting in Zomba at the beginning of May 1956, the Commission heard evidence at four meetings over four months in Zomba, Fort Johnston, Blantyre, and finally, Lilongwe. By November 1956, they had produced a final report on their findings.

Ref: TNA, MPG 1/1220/3

The geography of the inquiry surrounded the Lake’s southeast, where the vast majority of fishing effort was concentrated. Zomba and Blantyre (along with neighbouring Limbe) were the key urban markets for fish. Fort Johnston, on the lake shore, was the location of the dominant non-African fishing concerns, notably Christos Yiannakis’ firm. Lilongwe expanded this tight geography somewhat and provided access to testimony from people based in the west and northwest of Lake Nyasa around Salima, Kota Kota, and Nkata Bay.

The Commission gathered interlocutors in three ways. Firstly, the prominent fishing industry and government individuals were called to give evidence. Secondly, native authorities and government departments were asked to provide individuals representative of certain groups, such as ‘African’ low-income consumers or ‘African’ fishermen. Finally, adverts were also placed in both English and Chichewa government newspapers, encouraging the public to come forward to offer evidence. Whilst skewed towards commercial fishermen and government officials and framed by the colonial impulse to see individuals as embodiments of a generalised Africaness, the inquiry evidence contains diverse voices. Testimony from the ‘big men’ at the top of the industry sits alongside fishermen who spent more time repairing their only net than fishing with it, village headmen from the lake shore, and urban wage labourers concerned about the rising cost of their favourite fresh fish.

From this array of people asserting their position and needs within this evolving fishing industry, numerous interesting themes emerge that warrant further exploration. There are the more obvious questions related to the wider economy of fish that were explicitly dealt with by the inquiry: price controls, exportation, supply and demand, and preservation. However, other themes speak to the broader late colonial landscape, such as infrastructure, governance, nutrition, labour, public health, scientific expertise and knowledge creation.

The transcriptions of the meetings were made by the Commission’s secretary, P. B. Clewes. Notably, she is the only woman mentioned by name in the transcripts (although a number of interlocutors did reveal that it was their wives who did all the shopping at the fish market). This speaks to the masculine domination of the fishing industry in Nyasaland and the gendered production of knowledge in colonial society.

The original material is held in a single file (C.O.M. 9-3-1) at the Malawi National Archives in Zomba. It was collected for this project by Dr Bryson Nkhoma and transcribed by Dr Milo Gough. Please get in touch with any questions or queries regarding the material.

Downloads

Transcriptions of the Commission Meetings:

- Preliminary Meeting of the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry, Zomba, 3 May 1956

- Meeting of the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry, Zomba, 17 May 1956

- Meeting of the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry, Fort Johnston, 8-9 June 1956

- Meeting of the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry, Blantyre, 17-19 July 1956

- Meeting of the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry, Lilongwe, 21-22 August 1956

Please reference the transcriptions as:

Malawi National Archives, C.O.M. 9-3-1. Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry (1956). Transcribed by Milo Gough. Accessed via Lessons from Lake Malawi, https://www.lessonsfromlakemalawi.com.

The Report from the Commission of Inquiry into the Fishing Industry (1956) is also available here.

Further Reading

Wiseman Chijere Chirwa, “Fishing Rights, Ecology and Conservation along Southern Lake Malawi, 1920-1964,” African Affairs, 95:380 (1996), 351–77

John McCracken, “Fishing and the Colonial Economy: The Case of Malawi,” The Journal of African History, 28:3 (1987), 413–29